Freedom of thought, conscience, and religion: Hindu religion in Europe

Andrea Debak

University of Split

This Article is written by Andrea Debak, a Law Graduate of University of Split

INTRODUCTION

The right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion is one of the main human rights. Not to mention, that all over the world freedom of religion is under assault, with severe restrictions which are rising in all five major religions in recent period.

However, the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion implies that democratic societies must allow pluralism and enable individuals to express their individual beliefs and thoughts.

Hinduism is also known as Sanatana Dharma and it is one of the largest religions in the world and one with a very long history.

When we think in terms of Hinduism in Europe, in some ways, the freedom of thought, conscience, and religion is still more philosophical than implemented.

FREEDOM OF THOUGHT, CONSCIENCE, AND RELIGION - EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS

Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights prescribes the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion.

That means that every individual has the right to practise their religion and express their thoughts and at the same time their inner dignity and individuality are also being protected.

Article 9 also implies that police and public authorities cannot encroach on anyone's right to publicly express their religious views and other beliefs unless it offends and disrupts public order, morality, and health or restricts the freedoms and rights of other people.

Then again, Article 9 recognizes that belief systems are part of the identity of individuals and their perception of life and that respect for different beliefs and religions is central to tolerance in a pluralistic modern society.

Religious freedom encompasses a positive and a negative dimension: the right to believe and practice a religion, and the right not to believe. In addition, religious freedom includes an individual and a collective dimension. While religion is a matter of individual conscience, religious freedom also involves public manifestation and collective practice. All these dimensions are present in Article 9(1) ECHR, which sets forth that the right to freedom of religion includes ‘freedom to change (one’s) religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest (one’s) religion or belief, in worship, teaching, practice, and observance.’ All these dimensions need to be taken into consideration when analyzing religious freedom in connection with other fundamental rights.[1]

HINDUISM IN EUROPE

Notably, globalization has made Hinduism one of the main religions even in Europe with a Hindu presence in every country.

Mainstream European constitutional heritage about religious freedom –just as about other issues- has been reinforced by its shaping by the ECHR as interpreted and enforced by the ECtHR in Strasbourg, often in dialogue with national courts. Article 9 of the Convention deals with freedom of religion in the proper context of individual liberties – together with freedom of thought and conscience, to the extent of expressly providing also for the ‘freedom to change his religion or belief’ - as well as about the implications of its collective enjoyment through a plurality of ways (‘freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief, in worship, teaching, practice and observance’).[2]

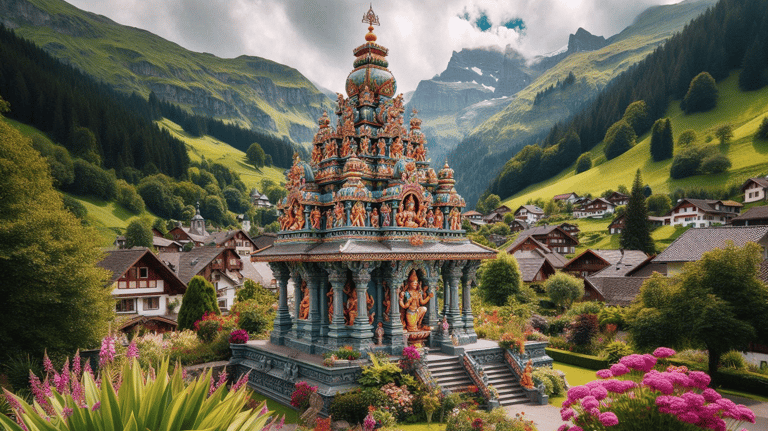

Significantly, in many European countries still, there are no public Hindu temples even though those pilgrimage places are necessary for Hindu practitioners but also tourists, and migrants and also to attract non-Hindus. It is important to make a good example for the regional plurality even in the diaspora and it should be possible to freely practice every major religion in every state.

Having that in mind, the establishment of temples is an important milestone in the development of Hindu communities in Europe as well as for social welfare, as they symbolize official Hinduism and a public place where practitioners of the Hindu religion can freely express their beliefs.

Historically, religion has been understood in European law as connected to national sovereignty. Previous indicates that religion carries an aspect of territoriality. Inherently, the main problem in Europe is that the State is not completely separated from the Church.

The church and the government in Europe should not interfere in each other’s domains. Even though the State should have equal distance from all religions, the influence of the government does extend to religious affairs in Western communities.

Thus, religious freedom is protected by legal orders, and for the Member States of the European Union it is protected and it is under the scope of European law, precisely under Article 9 ECHR.

Likewise, in Europe, the States do not offer any financial support to any religious organization. By contrast, in India, the State offers religious minorities the right to establish their religious institutions and organizations, and in some situations also extends assistance and financial support to these institutions.

The EU law (Framework Directive) specifically prohibits differential treatment based on religion only in employment (including vocational training). Other well-known areas from the EU directive prohibiting racial and ethnic discrimination (education, healthcare, provision of goods and services) are not covered.[3]

It is also worth recalling the case of Milanovic v. Serbia, 14 December 2010, in which the State was condemned for its passive stance regarding repeated physical violence perpetrated by extreme right-wing militants upon a representative of a national Hare Krishna Hindu Community. The Court recognized the violation of Articles 3 and 14 of ECHR and held: ‘[…] treating religiously motivated violence on an equal footing with cases that had no such overtones meant turning a blind eye 50 Joint action/96/443/JHA of 15 July 1996 adopted by the Council based on Article K.3 of the Treaty on European Union, concerning action to combat racism and xenophobia. 51 See, among others: Austrian Criminal Code, para. 283; Belgian Anti-Discrimination law 10th May 2007; Bulgarian Criminal Code, Article 162; Estonian Criminal Code, Article 152; Irish Prohibition of Incitement to Hatred Act 1989; Portuguese Criminal Code Article 240. 52 For example: Spanish Criminal Code, Article 22, para. 4, Luxembourg Criminal Code, Article 377. 40

Religious practice and observance in the EU Member States to the specific nature of acts that are particularly destructive of fundamental rights […] although the authorities had explored several leads proposed by Mr. Milanovic concerning the motivation of his attackers these steps amounted to little more than a pro forma investigation’[4]

CONCLUSION

The abuses of the right to freedom of thought, conscience, and religion are widespread and impact people throughout the world. The individuals who associate with religious communities and rreligious organizations must overcome increasing repression when they express their beliefs or manifest their religion in public.

If people are willing to cooperate they can make an impact and reverse the rising religious repression as well as strengthen the universal right to religious freedom, freedom of conscience, and freedom of thought for everyone.

Furthermore, it is important to understand the nature of the right to religious freedom and act against the ongoing threats to that right.

The easiest way to implementt these principles is by respecting the rights of all religions and beliefs, with discrimination towards none.

To put it in another way, wwithout freedom of thought, the realization of other rights is not possible.

Finally, practices of all religions and beliefs should work together to protect and promote freedom of religion and tolerance for all on the domestic and international levels.

“Religious and other beliefs and convictions are part of the humanity of every individual. They are an integral part of his personality and individuality. In a civilized society, individuals respect each other’s beliefs. This enables them to live in harmony.[5]

References:

[1]Directorate-general for internal policies, Policy department c., Citizens rights and constitutional affairs, Religious practice, and observance in the EU Member States, ’ Challenges in constitutional affairs in the new term: taking stock and looking forward,’2014.,

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2014/509992/IPOL_STU(2014)509992_EN.pdf accesed on 12 September 2024.

[2] Directorate-general for internal policies, Policy department c., Citizens rights and constitutional affairs, Religious practice, and observance in the EU Member States, ’ Challenges in constitutional affairs in the new term: taking stock and looking forward,’ 2014.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2014/509992/IPOL_STU(2014)509992_EN.pdf accesed on 12 September 2024.

[3] European Commission, ‘Proposal for a Council directive on implementing the principle of equal treatment between persons irrespective of religion or belief, disability, age or sexual orientation’, COM/2008/0426/FINAL, 2008, 2009., https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/note/join/2009/410670/IPOL-LIBE_NT(2009)410670_EN.pdf accessed on 12 September 2024.

[4] European Court on Human Rights, ‘Case of Milanovic v. Serbia’ (Application no. 44614/07) 2010. https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/fre#{%22itemid%22:[%22001-102252%22]}, accessed on 12 September 2024.

[5] House of Lords, UK Parliament, ‘Judgments - Regina v. Secretary of State for Education and Employment and others (Respondents) ex parte Williamson (Appellant) and others’, 2005., https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld200405/ldjudgmt/jd050224/will-1.htm, accesed on 12 September 2024.